An Autumn Mystery

A true tale from the mountains of Liechtenstein

You have no doubt heard the expression ‘things that go bump in the night’. It is a rather hackneyed collection of words, usually referring to tales of nocturnal visits by ghosts or poltergeists. Overuse has given it a tongue in cheek meaning.

Well, this autumn I had a strange and rather unnerving experience when something really did go bump in the night.

It was almost Halloween and, together with Mortimer my Fox Terrier, I had driven to Liechtenstein, the tiny principality nestled between Switzerland and Austria, to spend a quiet time in the mountains.

As it was the end of October, many of the leaves had already turned gold, russet and auburn. Approaching the small country, I was greeted by blue skies and bright sunshine.

At this time of year, one appreciates not only sunny days, but every minute of them because daylight is in short supply and the nights are long.

The clocks had been turned back just a few days ago so night time now started an hour earlier: by six o’clock it was dark.

I had rented a lovely chalet in the hamlet of Gaflei, a collection of a dozen or so houses at the end of a long road that zigzagged its way up a mountain.

The little wooden house was in typical alpine style with a gently sloping roof and overhanging eaves. On the side where the land rose behind the chalet, the roof was only a couple of metres off the ground.

Being set on a mountain, the building was split-level. Along the aspect facing the valley there was a long balcony on which a wooden table and a log bench provided the perfect place for taking in the mountain air while having breakfast.

My holiday home was the second to last building in the tiny settlement, beyond which a rough track continued past a field and into the forest towards a few isolated farmhouses even higher up the mountain. Occasionally, a car would go by, presumably on its way to or from one of the farmsteads.

This rustic cottage provided a welcome retreat from city life. Sets of small antlers adorned the walls, interspersed by a collection of stuffed mallard ducks, as if caught mid-flight. Nature was not just all around the house, but inside it too.

It also presented an opportunity for carefree walks with Mortimer, away from traffic, mountain bikes and crowds of ramblers.

We made our way along paths through silent pine forests and across mountain meadows. Here, the only noise was the gentle clanking of bells, traditionally hung round the necks of the grazing cattle to frighten away predators.

The toffee-coloured cows munched at the grass, ignoring us as I plodded on and Mortimer trotted by on his new extendable lead. It was a new purchase so that he would not get lost, despite his eyesight and hearing deteriorating with his advancing years.

Mountains are known for their quickly changing weather and autumn is a season of transition. As if to make the point, some days a blanket of cloud spread across the azure sky pulled by some invisible hand, replacing the bright autumn sunshine with cold rain.

When the weather was good, by day there were views from the chalet across the Rhine valley far below to the mountains of the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen on the other side. Here, the Rhine flows in an almost straight line along the valley from south to north.

It had once been a meandering river surrounded by water meadows. For centuries, the locals had eked out a living farming the valley floor.

Several times in the 19th and early 20th century, the Rhine burst its banks and flooded the narrow plain that lies between the mountains of Liechtenstein in the east and those of Switzerland to the west. To prevent further loss of life and livelihood, the river was eventually canalised, so that it now looks like a silver ribbon laid out along the valley floor.

Sitting on the balcony, it was just possible to make out Burg Gutenberg at the southern end of the valley near the Swiss border. A medieval castle perched atop a hill above the town of Balzers, after falling into ruin it was rebuilt by a local businessman early last century. Today, it would make a perfect setting for a vampire movie.

On less clement days, the valley was invisible, covered by a thick layer of cloud. Looking out from the window, there was nothing to suggest that anything at all existed beneath the fluffy white sea that stretched in front of me to the other side of the valley.

On such days, the my little wooden house and Gaflei found themselves above the clouds, giving the impression of being in a separate world.

I had been at the chalet a few days when ‘something’ came to pay a nighttime visit. It was the day before Halloween.

In the Christian calendar, Halloween marks the start of a three-day period of remembering the dead.

It begins on 31 October with All Hallows Eve or Halloween. 1 November is All Hallows or All Saints Day, when the dead are traditionally remembered and people visit the graves of the deceased. The third and final day – 2 November – is All Souls Day, a commemoration for those whose spirit is still in purgatory because of their sins.

Halloween has its origins, though, in the Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the end of the harvest season and the start of winter – the darker half of the year. Celts believed Samhain was a time when people, spirits and other creatures could more easily pass between this world and the next – the ‘Otherworld’.

The weather started off good and I was able to have my toast and morning coffee on the balcony. After tidying up the kitchen and walking Mortimer, I got in the car and headed down the long, winding road into the valley and across the Rhine into Switzerland.

I had decided to visit Werdenberg Castle, a walled medieval stronghold, and the tiny 800-year old village of the same name set along one side of the small lake in front of it.

Like the nearby Burg Gutenberg, the castle was built on top of a hill. The tourist season was coming to an end and there were only a few other people exploring the stone-floored chambers that had been lived in until the 1950s.

Some of the rooms, barely lit, had clockwork mechanisms hung from a collection of lamps suspended from the ceiling. Whirring and clicking, they projected disarmingly simple silhouettes of soldiers, peasants, horses and the grim reaper with his scythe. The black figures moved jerkily across the high stone walls while a recorded voice told of battles, repression, uprisings and plague.

After visiting the castle, I headed down the path that lead through the vineyards to Werdenberg village. Little more than a couple of streets, the collection of old wooden houses is home to only about 70 people.

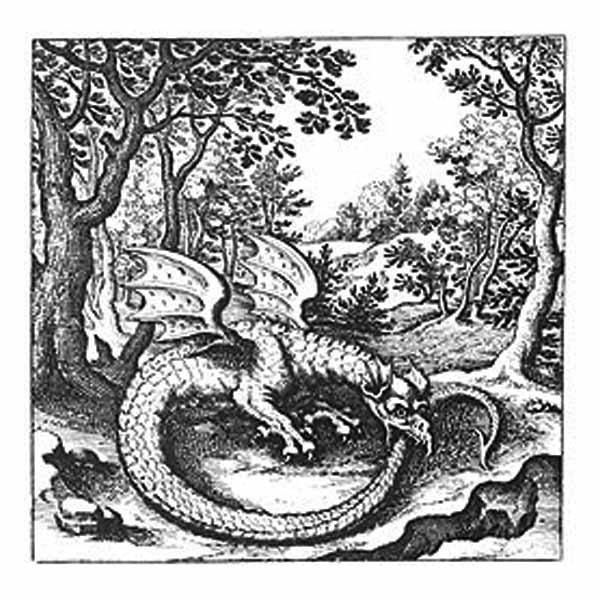

Its main attraction is the Schlangenhaus – the Snake House – so called because of the huge lindworms or mythical snakes-cum-dragons painted on its outer walls. I went inside to look at the displays detailing daily life in the village in years gone by.

In one of the corridors there was a series of old drawings of dragons and other mythical beasts that people had supposedly seen in the local forests and mountains at a time when the world still held many more mysteries and secrets. The artists clearly had great creative skills yet I wondered what they had actually seen to inspire such drawings.

By early afternoon a dark bank of cloud appeared over the mountains on the Swiss side of the valley. It soon began to rain so I decided to drive back to Liechtenstein.

It was not far as the crows flies but the drive up the mountain was inevitably slow, with its long series of hairpin bends. By the time I got back to the chalet, the light was fading fast.

The clouds from Switzerland were completing their advance and as night fell they descended silently to cover the hamlet, reducing visibility to just a few metres.

Peering out from the chalet’s kitchen window, as far as I could see there were no lights on in any of the other houses. Mortimer and I were alone.

I closed the white cotton curtains and decided to light a fire in the main room. I brought in some logs from the stack outside the front door and carefully arranged them in the hearth on top of paper, twigs and firelighters.

I put a match to my creation and soon a fire was crackling away. Orange flames danced over the logs like tiny demons and the smell of wood smoke drifted through the sitting room towards the kitchen and dining area.

Following a dinner of roast venison, potatoes and parsnips, I sat reading in front of the fire with a glass of Rioja. The only noise was the purring and occasional spitting of the fire.

After a while, I needed to get some more logs. I unlocked the front door and went out to the wood pile. Outside, all was quiet. The chalet was still surrounded by cloud so that beyond a few paces there was nothing more than a wall of white.

I hastened back indoors with my armful of firewood and closed the door.

The evening wore on. I looked at my watch. It was a quarter to eleven. I decided to retire upstairs. I let Mortimer out, using his new extendable lead so that he would not get lost in the thick cloud.

Once he was back inside, I locked the front door and headed upstairs. The bedroom was directly below the roof with the ceiling sloping on either side, giving it a cosy feel.

Mortimer quickly fell asleep on his cushion while I continued reading my book, a novel about the history of Liechtenstein.

Suddenly, there was an almighty BANG!

It sounded as if something very large and very heavy had just jumped on to the part of the roof immediately above the bed. It was so heavy the entire house shook.

Hardly daring to breathe, I looked up. I half expected to see the pine ceiling boards splinter as they gave way under the weight of whatever it was that had landed on them.

But nothing.

I waited and listened for something or someone walking on the roof. But there was no clattering of hooves, no thumping of feet, no growling, no talking – just silence.

What could make such a noise, I wondered? What would – or could – jump on to a roof? More to the point, what animal of such size would have the agility to do so?

I thought about the animals that lived in Liechtenstein. The largest and heaviest I could think of were cows, red deer and ibex. I could not imagine a cow leaping on to a roof and, although a deer or ibex might be capable of doing so, what would drive it to? And surely I would have heard the stamping of hooves after the initial thud?

If it were not some large herbivore with hooves, then that left large animals with paws. The possibilities were distinctly less appealing – bears or wolves, or perhaps some large cat escaped from a private collection.

I remembered reading somewhere that there are more tigers in private zoos in the world than there are left in the wild. Some of these large felines are kept illegally, so if they escape their owners are reluctant to inform the authorities to avoid getting into trouble. Could there possibly be a large cat prowling outside? Or curling up round the chimney in an effort to keep warm?

Of course, such ideas seemed fantastical but something had landed on the roof and had caused the entire chalet to shake. I was wide awake when it happened, so I knew I had not dreamed it.

Indeed, perhaps something had landed – or fallen – on the roof rather than leapt on it? Yet where would it fall from?

I recalled cases of corpses dropping out of the skies above London. These are the bodies of people from Africa or war torn countries, who in an attempt to start a new life stow away in the undercarriage of aircraft heading to Europe.

Unfortunately, they do not realise that the undercarriage compartments are not heated so they either freeze to death at temperatures of up to minus 50 degrees mid-flight or asphyxiate due to lack of oxygen.

As the aircraft approach London’s Heathrow Airport and lower their undercarriage, the frozen bodies drop out, landing in people’s gardens or sometimes on cars.

Yet the nearest major airport was in Zürich more than 100 kms away. I doubted aircraft lowered their wheels so soon before landing, so this scenario also seemed highly unlikely.

None of the possibilities, however implausible, held much appeal for going outside in the pitch black and thick cloud to explore. I realised I did not even have a torch.

Mortimer, all 10 kilos of him, would not be much help in fending off some large beast with green eyes, long claws and saliva dripping from huge fangs. Becoming deaf with old age, he had not even noticed the tremendous bang and continued to sleep blissfully.

I decided to wait until the following morning to investigate.

The next day was 31 October, Halloween. Despite the day’s creepy reputation, the cloud had lifted and I could once more see the other houses in Gaflei. The sun was out and much of the valley below was again visible between pockets of white floating half way up the mountain.

What a difference the day makes.

I went out to see if there were any clues as to the source of the nocturnal noise. There was, of course, no thawing corpse by the side of the chalet. Nor were there any footprints – animal or human – or signs of the grass having been trampled.

I looked up at the roof. Everything was intact: no missing tiles, no claw marks, no sleeping tiger curled round the chimney – nothing.

And yet something had caused the huge bang the night before and shaken the entire building.

I took advantage of the good weather to go for a walk with Mortimer. We took a path that lead out of the hamlet and which had the advantage of being more or less level. At the ripe old age of 16, my little dog finds walking uphill a challenge, even more so as he has a heart condition.

We left Gaflei and entered a stretch of pine forest. The sun struggled to get through the dense criss-cross of branches and we quickly found ourselves in the shadows. Was there, I wondered, some large animal wandering these woods, if not during the day then at night?

I remembered the old drawings in the Schlangenhaus of strange beasts that people once feared roamed the wilder parts of the Alps. Perhaps Liechtenstein had its own equivalent of the Loch Ness monster, a lindworm lurking in a mountain cave somewhere. It seemed a ridiculous thought but I could find no logical explanation for the previous night’s event.

Back at the chalet, I spent the rest of the day reading and writing and drinking coffee. Every now and then a few hikers would walk past, their boots crunching on the gravel, their hiking poles click-clacking in time. Once or twice a car drove past.

The light began to fade and before long the little collection of houses that is Gaflei once more drifted into darkness.

Again I lit a fire and had dinner. After I had finished washing up, I began wondering about what sort of animals actually lived in Liechtenstein. Perhaps there really were bears? I looked on the internet and quickly found a detailed report on the county’s mammals.

There had indeed once been bears in Liechtenstein, but none had been seen for decades. The same went for lynx: in years past, they too had roamed the principality’s uplands but had vanished from its territory, hunted out.

According to one website, though, lynx had returned to Liechtenstein and so had wolves. A lynx would have the agility to leap on to the roof but what I had heard the night before sounded much heavier – like bear-weight heavier. Bears, however, had still to make a reappearance, said the website. And yet there always had to be a first sighting…

Another website listed eye-witness reports of escaped black panthers in Switzerland and Bavaria.

The thought of opening the front door of the chalet and coming face to face with a wolf, a lynx or a panther was at best ‘interesting’. I had visions of Mortimer going out on his extendable lead and only the lead coming back.

One of the authors of the report on the mammals of Liechtenstein also appeared on an environmental website, along with contact details. Apparently, he was also a member of the hunting community, so I reckoned if anyone knew what was roaming the mountains and forests of this tiny country, he would.

I wrote to him, describing the experience of the night before and floating my ideas as to what might have caused it. Bears and lynxes seemed unlikely, I thought. Perhaps a large feline escaped from a private zoo? I finished by asking him to let me know his thoughts and whether he had received any similar reports.

Perhaps whatever it was had made its way past farms and villages, leaving large paw prints and a trail of half-eaten goats in its path. I did not suggest this but the thought crossed my mind.

Would the beast return at the same time, I wondered? After all, many animals are creatures of habit. So that evening, not without trepidation, I let Mortimer out on his lead well before eleven o’clock. I was very glad when he trotted back.

The evening and the night passed without event. Nothing stomped over the roof, nothing scratched at the window, nothing snorted on the other side of the front door.

The next morning, I was to have the answer to the mystery.

While having my breakfast, I checked my emails and there was already a reply to my enquiry to the expert in Liechtenstein’s wildlife.

It read:

Dear Mr Ratchford,

It was an earthquake.

Kind regards.

An earthquake? In Liechtenstein?

I felt both relieved and rather silly: relieved that I was not vacationing in an alpine version of Jurassic Park but rather silly at how I had let my imagination run away with me.

A few days later, I recounted the story to a Californian friend. She explained that as well as horizontal earthquakes where everything moves from side to side, there are also vertical quakes where tension built up between tectonic plates is suddenly released in a single downward movement.

This explained the loud bang and why the chalet had shaken without all the furniture sliding around as would happen in a horizontal quake or a Hollywood movie. It was also why there were no further noises after the first heart-stopping thud.

I checked the internet. Yes, there had been an earthquake in Liechtenstein that evening with its epicentre 4 km underneath the very mountain on which Gaflei lies. It was only 2.8 on the Richter scale but that had been enough to shake the chalet – and my nerves.

Sometimes things really do go bang in the night but they are not always what they seem. Nor do they necessarily involve ghosts, poltergeists or other creations of the imagination. Perhaps a similar experience had fuelled the artistic impressions of those who in centuries past had sketched the pictures of the mythical monsters of the mountains.

I had many expectations of my trip to Liechtenstein – an earthquake was not one of them.

RETURN