East Greenland

Wild and Remote

At the end of the summer, I headed off for a short trip to Greenland. An autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, it is the largest island in the world. It is also the most sparsely populated country in the world with a population of less than 57,000.

Although the flight from the Icelandic capital Reykjavik – where I stopped off on the way – took less than two hours, I was surprised to find myself crossing two time zones. This was because the farther north one travels, the narrower the time zones become until they finally converge at the north pole.

The propeller plane flew to Kulusuk, a settlement of 200 souls on an island off the east coast of Greenland. As we came into land, the Fokker 50 was buffeted by hair-raisingly strong winds and driving rain. I had planned to carry on by helicopter to Tasiilaq on the mainland, with a population of 2000 the designated capital of East Greenland. The weather was so bad, though, that the helicopter could not take off from Tasiilaq to come to the airport; nor could the plane fly back to Iceland.

Along with the other marooned travellers, I spent a night in the Kulusuk Hotel, a building in the middle of nowhere. Holed up with a group of strangers and listening to the howling wind, I felt it seemed like a perfect place for an Agatha Christie-style murder, but come the morning everyone was still alive. Even better, it had stopped raining and the sun had come out.

The helicopter arrived and we were soon flying over the sapphire blue sea on our way to Tasiilaq. Below, small icebergs – the last survivors of the summer – drifted south.

Tasiilaq means ‘like a lake’ in East Greenlandic, the language spoken here. The official national language is West Greenlandic, which children have to learn in school. Danish is the first ‘foreign’ language. For the locals, I realised, English was their fourth language.

The small town is made up of brightly coloured houses clinging to the rugged hills that rise up from the fjord. The original settlers here were Inuit who arrived in the 14th and 15th centuries. The tough climate meant life was difficult and towards the end of the 19th century a combination of factors led to there being fewer than 300 Inuit left. In 1894, the Danish government set up a trading station in Tasiilaq, conditions began to improve and the population recovered.

Today, life is a mixture of modern and traditional. Fish caught in the icy fjord hang out to dry in the arctic air and tethered husky dogs bark; locals drive around in 4x4s and enjoy a pizza at one of the town’s few eateries. To the visitor arriving from a big city, Tasiilaq’s amenities may seem limited, but it has most things the surrounding population needs and is kept supplied by 6-8 ships a year.

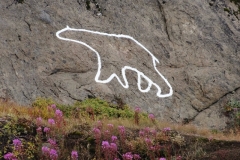

In late summer, I discovered, much of the southern coast of Greenland is brown, not green as its name suggests or white as one might imagine. The snow has melted and the soils are too thin to support much vegetation; coarse grass and small arctic flowers add a touch of colour. Heading out of town, one is quickly in wilderness. Nature here is harsh and unforgiving, even in summer.

Having had a glimpse of a small corner of this vast land, I am keen to return. Next time it will be to the western coast and in springtime when the snow is still on the ground.

RETURN